The Po Hing Fong Disaster in 1925

15 May 2017

With a hilly terrain, Hong Kong is prone to the hazards of landslides during rainstorms, in particular for steep slopes in developed areas. Over the years, there were severe rainstorm events in Hong Kong that triggered disastrous landslides and resulted in heavy loss of lives. Apart from the notorious landslide events in 1966 and 1972[1, 2], another catastrophic incident in the early part of Hong Kong history occurred in 1925 at Po Hing Fong, a quiet and luxurious residential area in the mid-levels near Caine Road on Hong Kong Island.

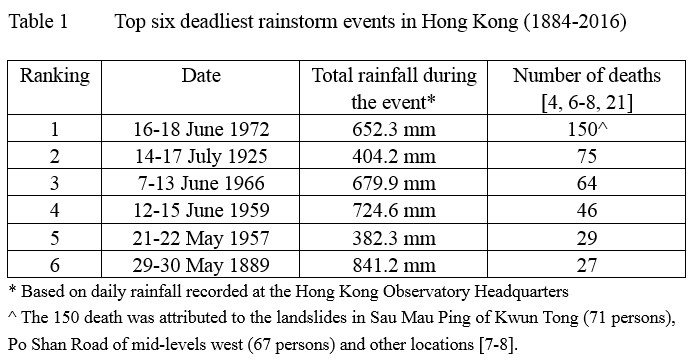

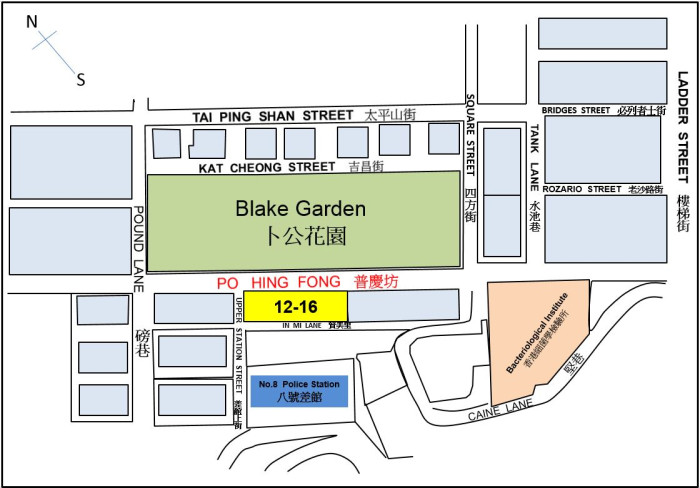

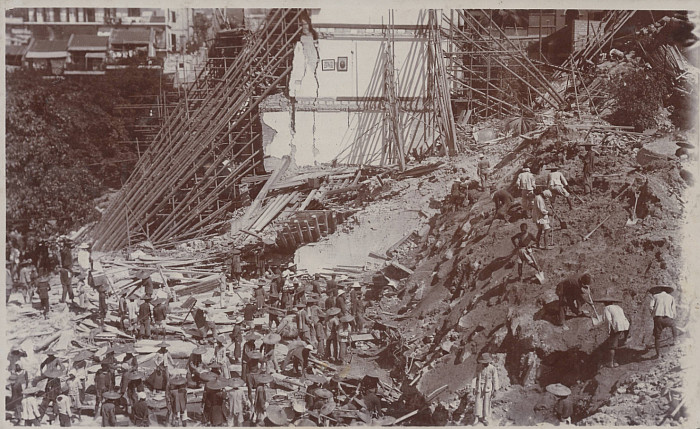

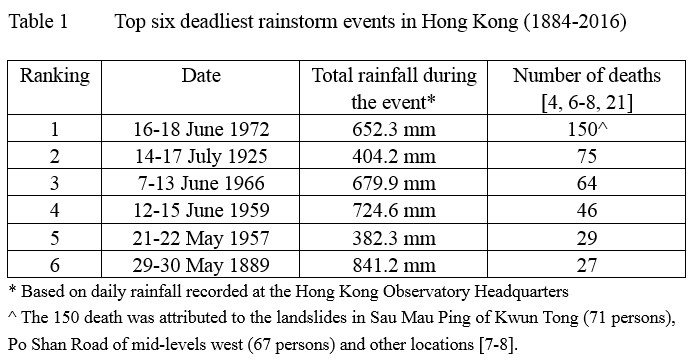

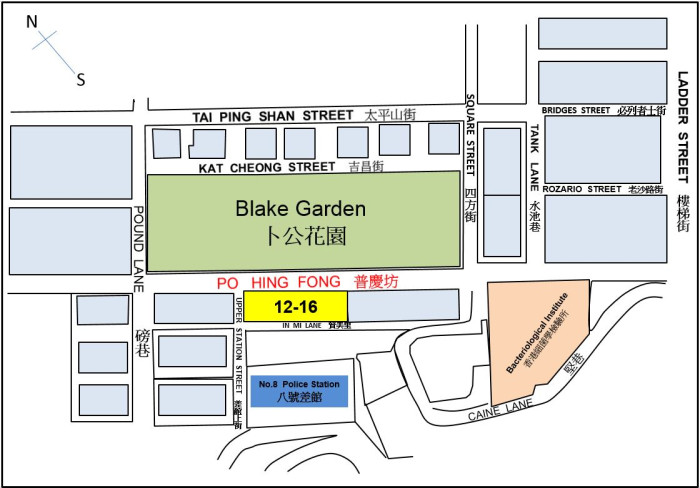

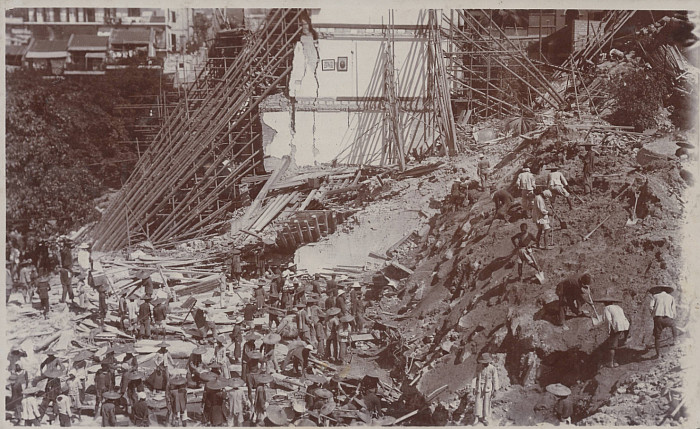

At round 9 a.m. on 17 July 1925, the retaining wall of In Mi Lane[3]which was beneath Caine Road collapsed after days of heavy rain. Large amount of debris ran down to Po Hing Fong and swept away seven four-storey houses from No. 12 to No. 16 (see Figures 1 and 2) with some thirty families inside, causing 75 death in this tragic event[4]. The victims of this incident were all rich merchants and influential dignitaries, including Mr Chau Siu Ki, J.P., owner of No.12, former Chairman of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals and a former member of the Legislative Council, and most of his family members in total 11 persons. His son, Sir Chau Tsun-nin, CBE, survived in this disaster. He was later appointed as a member of Executive Council and Legislative Council, and was knighted in 1956. For No.13-14, the owner was a descendant of Mr Chiu Yu-tin, one of the founders of Nam Pak Hong and the third Chairman of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. No.15 was owned by Mr Wong Pak San who was a tycoon and a former Principal Director of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. At the time, this was the deadliest rainstorm in the early days of Hong Kong which hit the headlines of many local newspapers[5]and aroused major concern in the community. The event is also keeping the record of the highest mortality in a single landslide event in Hong Kong (see Table 1).

Figure 1A rough sketch of the street map around Po Hing Fong in the 1920s.

Figure 2Workers clearing away the debris of the collapsed retaining wall and houses at Po Hing Fong in July 1925 (photo courtesy of Mr C M Shun).

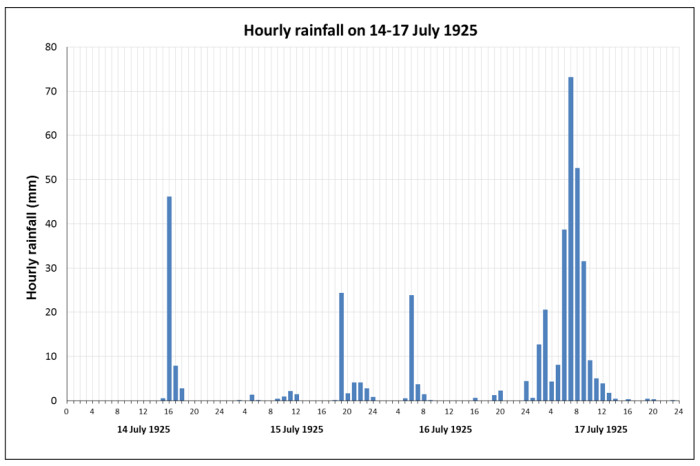

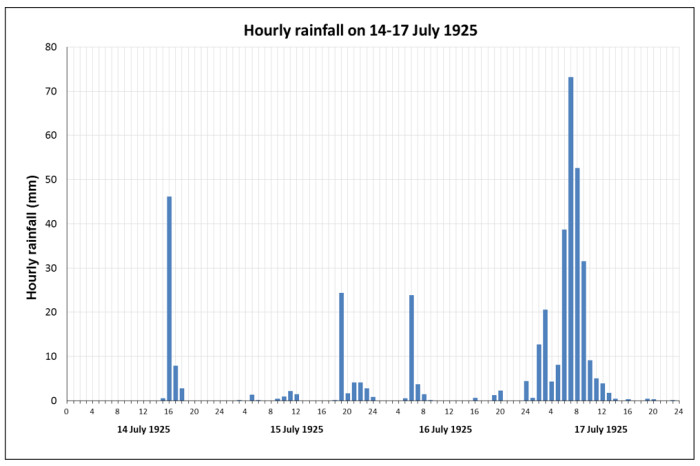

As shown in Figure 3, the weather in Hong Kong was unsettled with occasional heavy showers from 14 to 16 July 1925 with a total of about 140 mm of rainfall recorded at the Observatory during the period. The weather deteriorated further with torrential rain in the early morning on 17 July and by 9 a.m., more than 240 mm of rainfall had fallen at the Observatory since midnight. Overall, the total rainfall during the period of 14 - 17 July at the Observatory was around 404 mm. While there was no rainfall station near the site at Po Hing Fong, the total rainfall recorded at the Botanic Garden from 14 to 17 July 1925 was about 436 mm (17.17 inches) according to reports by the Botanical and Forestry Department at the time[9], suggesting that the rainfall amount over Hong Kong Island during the period was likely to be comparable or slightly higher than that recorded at the Observatory in Tsim Sha Tsui.

Figure 3Hourly rainfall recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory from 14 to 17 July 1925

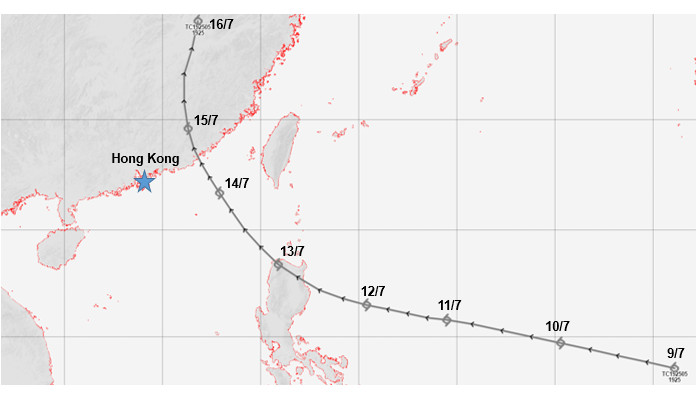

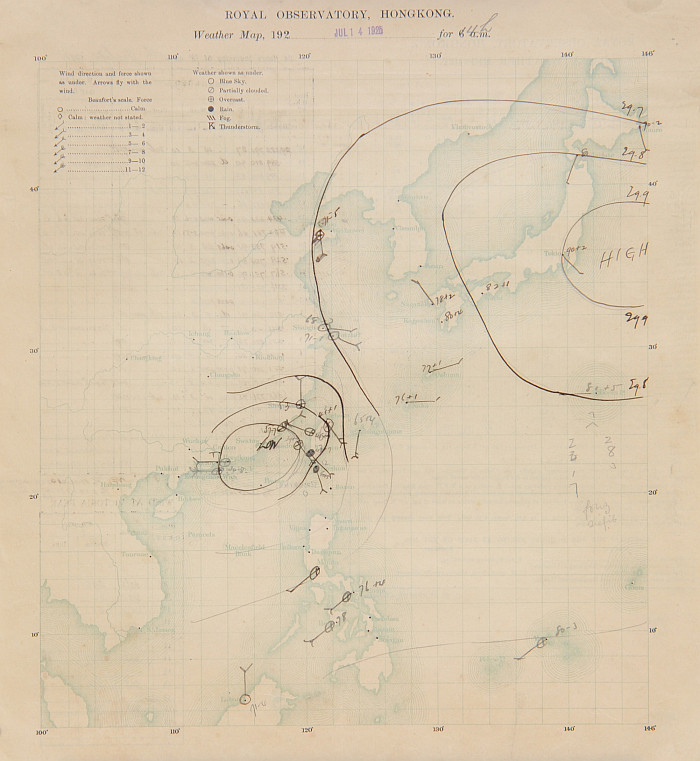

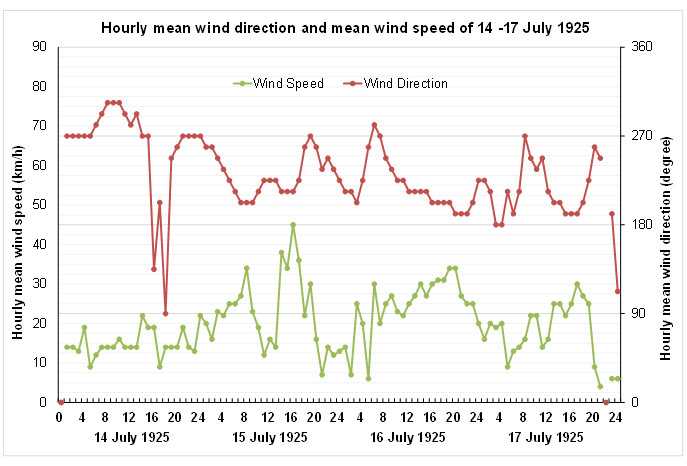

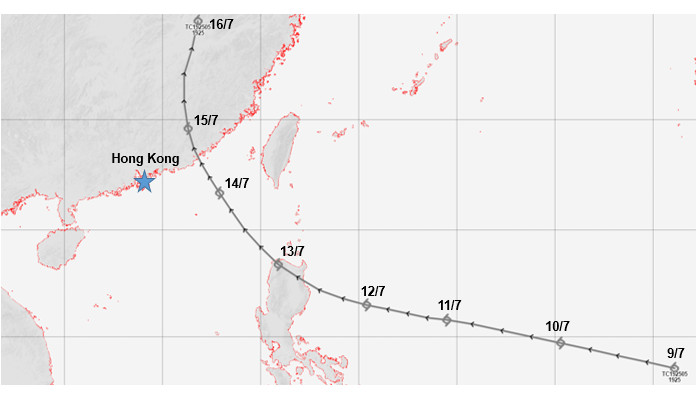

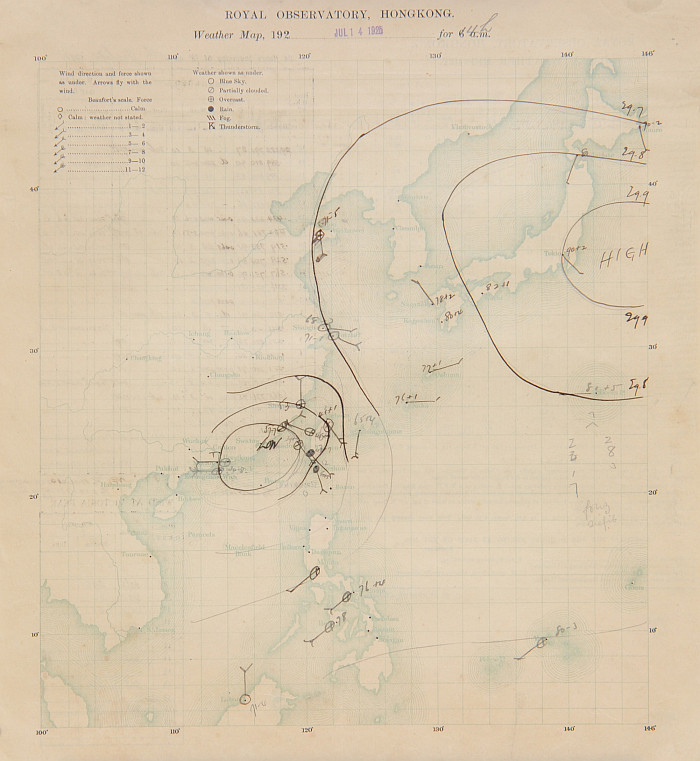

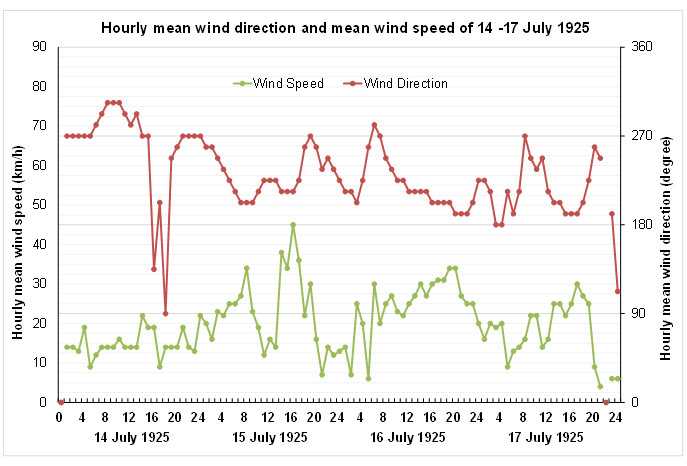

Looking back at the weather charts, a tropical cyclone made landfall to the east of Hong Kong near Shantou on the night of 14 July and tracked northwards, weakening over eastern China in the next couple of days (Figure 4). The southwest monsoon affecting the coastal area of Guangdong strengthened in the wake of the landfalling tropical cyclone and brought unsettled weather to Hong Kong on 14-17 July (Figures 5 to 7). The Hong Kong Observatory hoisted the local storm signal No. 5 (meaning at the time Gale winds expected to affect Hong Kong from the west) between 4:10 a.m. on 14 July and 10:00 a.m. on 15 July. Coincidently, this was very similar to the main cause behind the historical rainstorm event that occurred just over a year later in 1926 after another tropical cyclone made landfall near Shantou[10]. However, it sounds a bit strange that, according to the track of the tropical cyclones at the time, both storms continued to tracking north after making landfall to the east of Hong Kong, but they still caused heavy rain in Hong Kong. This may not be in line with our general understanding that the heavy rain in Hong Kong induced by the strengthening of the southwest monsoon usually occurs when a tropical cyclone moves west to the north of Hong Kong (at 115oE or its west) after making landfall to the northeast of Hong Kong[11]. Did these two tropical cyclones which brought disastrous rainstorms to Hong Kong come closer to the north of Hong Kong than what were depicted in the historical records of the Observatory? It may be a subject of further research.

Figure 4Track of the tropical cyclone from 9 to 16 July 1925 that affected the landslide at Po Hing Fong.

Figure 5Weather chart at 1400 H on 14 July 1925.

Figure 6Weather chart at 0600 H on 17 July 1925.

Figure 7Hourly mean wind speed and direction recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory on 14-17 July 1925. The wind speeds were calculated from data recorded by the Beckley anemometer at HKO Headquarters and the conversion factors from HKO Technical Note No. 66[12].

During the inquest in the Coroner's court, Mr Charles William Jeffries, the then Acting Director of the Hong Kong Observatory, analyzed the rainfall records in June and July, and indicated that while the rainfall of this event was not unprecedented, it was also not common. A similar quantity had only been recorded on three occasions previously in 1885, 1891 and 1892. There would not be much difference between the rainfall at Po Hing Fong and the Hong Kong Observatory on that day[13]. Summarizing the evidence and statements from the expert witnesses and the engineers of the Public Works Department, the collapse of the retaining wall was mainly attributed to inadequate safety margin of the retaining wall, deficiency in drainage system and judgment error in the retaining wall inspection in 1923. The court also offered the following recommendations for improvement[14]:

Later on the Legislative Council passed in its meeting on 24 September 1925 a funding of HKD 241,750 for the repair of the rainstorm damages[15]. In the Legislative Council meeting on 22 October 1925, the Government committed to conduct systematic inspection of retaining walls in different districts. As the Government was not obligated to use public funds to maintain private retaining walls, they will inform the owners of the retaining walls with problems to carry out the repair work [16]. Canadian geologist, Dr William Lawrence Uglow, arrived at Hong Kong to conduct a comprehensive geological survey on 6 November 1925 and submitted a study report on 21 April 1926. He pointed out that the weathered granite can be very vulnerable and the retaining wall of Po Hing Fong was a typical example of this[17]. While the report mainly focused on the feasibility of developing underground water resources, it could be considered as a response by the Government to the recommendation of establishing the committee of experts.

Although the rainstorm in 1926 set a historical rainfall record, it was relatively less deadly than that of 1925[10]. As such, the proposed amendment of the Building Ordinances was not submitted to the Legislative Council until 1935. The amendment was then passed with a number of new measures including regulations on the construction of foundations, restricting the maximum height of a retaining wall to 25 metres, at least one weep hole of not less than 75 millimetres in diameter for every three square metres, installing a hydrophobic layer at the back of each retaining wall, accompanying the design with a stress diagram, and increasing the fine to 500 dollars for any offence against the Building Ordinances[18].

Concluding remarks

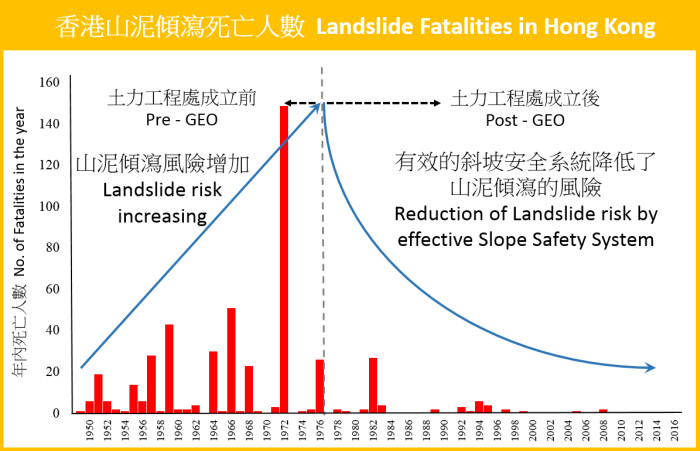

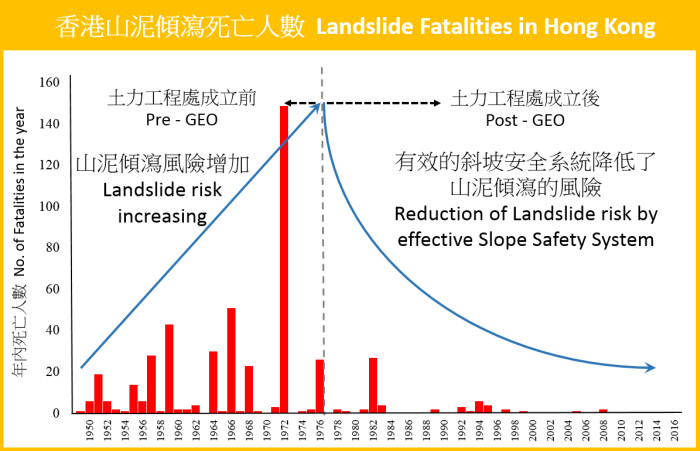

The Po Hing Fong disaster in 1925 is still a record keeper of the highest death toll in a single landslide event in Hong Kong. Although the rainstorm did not set a new rainfall record, the disastrous landslide occurred due to inadequate safety margin of the retaining wall, deficiency in drainage system and judgment error of the retaining wall inspection. Given the concerned retaining wall was designed over a century ago (referring to the completion time) and the relatively primitive geotechnical engineering knowledge at the time when compared with the present day, the below par safety margin of the retaining wall was only a post-event assessment and not totally the fault of the then engineers. Accidents and disasters are usually the result of a combination of factors rather than a single one. Coincidentally, the accumulated rainfall of the rainstorm on 18 June 1972 was also not extreme enough to break any historical record[19], but the induced landslides resulted in the highest mortality in the history of Hong Kong. Since the Government established the Geotechnical Engineering Office (GEO) in 1977, the upgrading and maintenance work of man-made slopes had improved significantly with a noticeable decrease in the number of landslide fatalities (Figure 8). This truly demonstrates that the Government has been working in the right direction for slope safety and landslide prevention.

Against the background of climate change, extreme weather events including heavy rain are expected to become more frequent, posing a great challenge to the safety of natural slopes[20]. With a view to preparing Hong Kong for the climate change challenges, we have to learn from the historical lessons to improve prevention measures and make a concerted effort to better the slope safety and maintenance work. Moreover, we should promote public awareness and enhance the resilience of the community against the risk of natural terrain landslides in Hong Kong.

Figure 8Landslide fatalities in Hong Kong (Data source : GEO)

T. C. Lee, K.Y. Ma* and C.M. Shun

(* Mr K.Y. Ma is a retired government engineer and also an enthusiast in the history of engineering in Hong Kong. He is currently Adjunct Associate Professor at the Department of Real Estate and Construction, University of Hong Kong)

References :

[1] T. Y. Chen, 1969 : The severe rainstorms in Hong Kong during June 1966, Supplement to Meteorological Results 1966, Royal Observatory, Hong Kong

[2] T. T. Cheng and Martin C. Yerg, Jr, 1979 : The severe rainfall occasion, 16-18 1972, Royal Observatory Technical Note No. 51.

[3] In Mi Lane is no longer exist nowadays

[4] Report of the Director of Public Works for the year 1925 https://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkgro/view/a1925/576.pdf

[5] South China Morning Post and 華僑日報 on 18 July 1925; the China Mail, and Hong Kong Daily Press on 20 July 1925

[6] Ho Pui-yin, 2003: "Weathering the Storm: Hong Kong Observatory and Social Development", Hong Kong University Press, 364 pp

[7] Unforgettable Incidents @ Kwun Tong, https://mmis.hkpl.gov.hk/kt_03

[8] Yang, T. L., S. Mackey and E. Cumine, Final Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Rainstorm Disasters 1972, GEO Report No. 229

[9] Report on the Botanical and Forestry Department for the Year 1925, Appendix N to Hong Kong Administrative Report for 1925. https://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkgro/view/a1925/573.pdf

[10] The Phenomenal Rainstorm in 1926 https://www.hko.gov.hk/blog/en/archives/00000135.htm

[11] Lam, H.K., 1975: The August rainstorms of 1969 and 1972 in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Observatory Technical Note No. 40

[12] W.C. Poon, HKO Technical Note No. 66, 1982: Tropical cyclone causing persistent gales at the Royal Observatory 1884-1957 and at Waglan Island 1953-1980

[13] Hong Kong Daily Press, the China Mail and Hong Kong Telegraph on 25 July 1925

[14] Hong Kong Telegraph on 5 September 1925

[15] Report of Hong Kong Legislative Council Meeting on 24 September 1925

[16] Report of Hong Kong Legislative Council Meeting on 22 October 1925

[17] WL Uglow, Geology and Mineral Resources of the Colony of Hong Kong, 1926

[18] Hong Kong Government Gazette, No. 300, 12 April 1935

[19] There were three consecutive days with daily rainfall exceeding 200 millimetres on 16-18 July 1972, unprecedented in the record of the Hong Kong Observatory

[20] GEO, 2016 : Natural Terrain Landslide Hazards in Hong Kong https://www.cedd.gov.hk/eng/publications/geo/naturalterrain.html

[21] Telegram from the Governor of Hong Kong to the Secretary of State on 30 May 1957, reporting the damages of the rainstorm on 22 May 1957

At round 9 a.m. on 17 July 1925, the retaining wall of In Mi Lane[3]which was beneath Caine Road collapsed after days of heavy rain. Large amount of debris ran down to Po Hing Fong and swept away seven four-storey houses from No. 12 to No. 16 (see Figures 1 and 2) with some thirty families inside, causing 75 death in this tragic event[4]. The victims of this incident were all rich merchants and influential dignitaries, including Mr Chau Siu Ki, J.P., owner of No.12, former Chairman of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals and a former member of the Legislative Council, and most of his family members in total 11 persons. His son, Sir Chau Tsun-nin, CBE, survived in this disaster. He was later appointed as a member of Executive Council and Legislative Council, and was knighted in 1956. For No.13-14, the owner was a descendant of Mr Chiu Yu-tin, one of the founders of Nam Pak Hong and the third Chairman of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. No.15 was owned by Mr Wong Pak San who was a tycoon and a former Principal Director of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. At the time, this was the deadliest rainstorm in the early days of Hong Kong which hit the headlines of many local newspapers[5]and aroused major concern in the community. The event is also keeping the record of the highest mortality in a single landslide event in Hong Kong (see Table 1).

Figure 1A rough sketch of the street map around Po Hing Fong in the 1920s.

Figure 2Workers clearing away the debris of the collapsed retaining wall and houses at Po Hing Fong in July 1925 (photo courtesy of Mr C M Shun).

As shown in Figure 3, the weather in Hong Kong was unsettled with occasional heavy showers from 14 to 16 July 1925 with a total of about 140 mm of rainfall recorded at the Observatory during the period. The weather deteriorated further with torrential rain in the early morning on 17 July and by 9 a.m., more than 240 mm of rainfall had fallen at the Observatory since midnight. Overall, the total rainfall during the period of 14 - 17 July at the Observatory was around 404 mm. While there was no rainfall station near the site at Po Hing Fong, the total rainfall recorded at the Botanic Garden from 14 to 17 July 1925 was about 436 mm (17.17 inches) according to reports by the Botanical and Forestry Department at the time[9], suggesting that the rainfall amount over Hong Kong Island during the period was likely to be comparable or slightly higher than that recorded at the Observatory in Tsim Sha Tsui.

Figure 3Hourly rainfall recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory from 14 to 17 July 1925

Looking back at the weather charts, a tropical cyclone made landfall to the east of Hong Kong near Shantou on the night of 14 July and tracked northwards, weakening over eastern China in the next couple of days (Figure 4). The southwest monsoon affecting the coastal area of Guangdong strengthened in the wake of the landfalling tropical cyclone and brought unsettled weather to Hong Kong on 14-17 July (Figures 5 to 7). The Hong Kong Observatory hoisted the local storm signal No. 5 (meaning at the time Gale winds expected to affect Hong Kong from the west) between 4:10 a.m. on 14 July and 10:00 a.m. on 15 July. Coincidently, this was very similar to the main cause behind the historical rainstorm event that occurred just over a year later in 1926 after another tropical cyclone made landfall near Shantou[10]. However, it sounds a bit strange that, according to the track of the tropical cyclones at the time, both storms continued to tracking north after making landfall to the east of Hong Kong, but they still caused heavy rain in Hong Kong. This may not be in line with our general understanding that the heavy rain in Hong Kong induced by the strengthening of the southwest monsoon usually occurs when a tropical cyclone moves west to the north of Hong Kong (at 115oE or its west) after making landfall to the northeast of Hong Kong[11]. Did these two tropical cyclones which brought disastrous rainstorms to Hong Kong come closer to the north of Hong Kong than what were depicted in the historical records of the Observatory? It may be a subject of further research.

Figure 4Track of the tropical cyclone from 9 to 16 July 1925 that affected the landslide at Po Hing Fong.

Figure 5Weather chart at 1400 H on 14 July 1925.

Figure 6Weather chart at 0600 H on 17 July 1925.

Figure 7Hourly mean wind speed and direction recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory on 14-17 July 1925. The wind speeds were calculated from data recorded by the Beckley anemometer at HKO Headquarters and the conversion factors from HKO Technical Note No. 66[12].

During the inquest in the Coroner's court, Mr Charles William Jeffries, the then Acting Director of the Hong Kong Observatory, analyzed the rainfall records in June and July, and indicated that while the rainfall of this event was not unprecedented, it was also not common. A similar quantity had only been recorded on three occasions previously in 1885, 1891 and 1892. There would not be much difference between the rainfall at Po Hing Fong and the Hong Kong Observatory on that day[13]. Summarizing the evidence and statements from the expert witnesses and the engineers of the Public Works Department, the collapse of the retaining wall was mainly attributed to inadequate safety margin of the retaining wall, deficiency in drainage system and judgment error in the retaining wall inspection in 1923. The court also offered the following recommendations for improvement[14]:

- Examine retaining walls in the vicinity thoroughly and take immediate steps to strengthen and / or rebuild;

- Appoint a commission of experts to investigate and improve the responsibility and supervision by the Public Works Department of all roads and buildings and nearby hillsides or retaining walls as well as relevant drainage systems; and

- Members of the commission must be independent experts and be empowered to propose amendments in Building Ordinances.

Later on the Legislative Council passed in its meeting on 24 September 1925 a funding of HKD 241,750 for the repair of the rainstorm damages[15]. In the Legislative Council meeting on 22 October 1925, the Government committed to conduct systematic inspection of retaining walls in different districts. As the Government was not obligated to use public funds to maintain private retaining walls, they will inform the owners of the retaining walls with problems to carry out the repair work [16]. Canadian geologist, Dr William Lawrence Uglow, arrived at Hong Kong to conduct a comprehensive geological survey on 6 November 1925 and submitted a study report on 21 April 1926. He pointed out that the weathered granite can be very vulnerable and the retaining wall of Po Hing Fong was a typical example of this[17]. While the report mainly focused on the feasibility of developing underground water resources, it could be considered as a response by the Government to the recommendation of establishing the committee of experts.

Although the rainstorm in 1926 set a historical rainfall record, it was relatively less deadly than that of 1925[10]. As such, the proposed amendment of the Building Ordinances was not submitted to the Legislative Council until 1935. The amendment was then passed with a number of new measures including regulations on the construction of foundations, restricting the maximum height of a retaining wall to 25 metres, at least one weep hole of not less than 75 millimetres in diameter for every three square metres, installing a hydrophobic layer at the back of each retaining wall, accompanying the design with a stress diagram, and increasing the fine to 500 dollars for any offence against the Building Ordinances[18].

Concluding remarks

The Po Hing Fong disaster in 1925 is still a record keeper of the highest death toll in a single landslide event in Hong Kong. Although the rainstorm did not set a new rainfall record, the disastrous landslide occurred due to inadequate safety margin of the retaining wall, deficiency in drainage system and judgment error of the retaining wall inspection. Given the concerned retaining wall was designed over a century ago (referring to the completion time) and the relatively primitive geotechnical engineering knowledge at the time when compared with the present day, the below par safety margin of the retaining wall was only a post-event assessment and not totally the fault of the then engineers. Accidents and disasters are usually the result of a combination of factors rather than a single one. Coincidentally, the accumulated rainfall of the rainstorm on 18 June 1972 was also not extreme enough to break any historical record[19], but the induced landslides resulted in the highest mortality in the history of Hong Kong. Since the Government established the Geotechnical Engineering Office (GEO) in 1977, the upgrading and maintenance work of man-made slopes had improved significantly with a noticeable decrease in the number of landslide fatalities (Figure 8). This truly demonstrates that the Government has been working in the right direction for slope safety and landslide prevention.

Against the background of climate change, extreme weather events including heavy rain are expected to become more frequent, posing a great challenge to the safety of natural slopes[20]. With a view to preparing Hong Kong for the climate change challenges, we have to learn from the historical lessons to improve prevention measures and make a concerted effort to better the slope safety and maintenance work. Moreover, we should promote public awareness and enhance the resilience of the community against the risk of natural terrain landslides in Hong Kong.

Figure 8Landslide fatalities in Hong Kong (Data source : GEO)

T. C. Lee, K.Y. Ma* and C.M. Shun

(* Mr K.Y. Ma is a retired government engineer and also an enthusiast in the history of engineering in Hong Kong. He is currently Adjunct Associate Professor at the Department of Real Estate and Construction, University of Hong Kong)

References :

[1] T. Y. Chen, 1969 : The severe rainstorms in Hong Kong during June 1966, Supplement to Meteorological Results 1966, Royal Observatory, Hong Kong

[2] T. T. Cheng and Martin C. Yerg, Jr, 1979 : The severe rainfall occasion, 16-18 1972, Royal Observatory Technical Note No. 51.

[3] In Mi Lane is no longer exist nowadays

[4] Report of the Director of Public Works for the year 1925 https://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkgro/view/a1925/576.pdf

[5] South China Morning Post and 華僑日報 on 18 July 1925; the China Mail, and Hong Kong Daily Press on 20 July 1925

[6] Ho Pui-yin, 2003: "Weathering the Storm: Hong Kong Observatory and Social Development", Hong Kong University Press, 364 pp

[7] Unforgettable Incidents @ Kwun Tong, https://mmis.hkpl.gov.hk/kt_03

[8] Yang, T. L., S. Mackey and E. Cumine, Final Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Rainstorm Disasters 1972, GEO Report No. 229

[9] Report on the Botanical and Forestry Department for the Year 1925, Appendix N to Hong Kong Administrative Report for 1925. https://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkgro/view/a1925/573.pdf

[10] The Phenomenal Rainstorm in 1926 https://www.hko.gov.hk/blog/en/archives/00000135.htm

[11] Lam, H.K., 1975: The August rainstorms of 1969 and 1972 in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Observatory Technical Note No. 40

[12] W.C. Poon, HKO Technical Note No. 66, 1982: Tropical cyclone causing persistent gales at the Royal Observatory 1884-1957 and at Waglan Island 1953-1980

[13] Hong Kong Daily Press, the China Mail and Hong Kong Telegraph on 25 July 1925

[14] Hong Kong Telegraph on 5 September 1925

[15] Report of Hong Kong Legislative Council Meeting on 24 September 1925

[16] Report of Hong Kong Legislative Council Meeting on 22 October 1925

[17] WL Uglow, Geology and Mineral Resources of the Colony of Hong Kong, 1926

[18] Hong Kong Government Gazette, No. 300, 12 April 1935

[19] There were three consecutive days with daily rainfall exceeding 200 millimetres on 16-18 July 1972, unprecedented in the record of the Hong Kong Observatory

[20] GEO, 2016 : Natural Terrain Landslide Hazards in Hong Kong https://www.cedd.gov.hk/eng/publications/geo/naturalterrain.html

[21] Telegram from the Governor of Hong Kong to the Secretary of State on 30 May 1957, reporting the damages of the rainstorm on 22 May 1957