To the East, To the West? (Effects of Landfall Position)

To the East, To the West? (Effects of Landfall Position)

KONG Wai

June 2011

Usually starting from May every year, Hong Kong will be prone to the impacts of tropical cyclones of different strength. The frequency peaks between July and September. In general, apart from the intensity of the tropical cyclone, winds will become more violent and rain will be more persistent when the centre of the storm or the associated spiral rainbands draw closer to Hong Kong. However, owing to the structure of the tropical cyclone and orographic effect, the weather affecting Hong Kong is also determined by the landfall location of the storm. Generally speaking, tropical cyclones making landfall to the west of Hong Kong often bring more severe weather to our region than those land to our east. The reasons are elaborated below.

Semicircle Effect

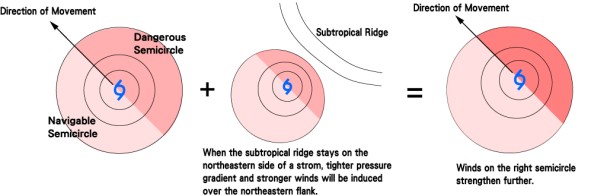

In the Northern Hemisphere, winds surrounding a tropical cyclone blow in an anticlockwise direction. Imagining if a tropical cyclone is divided into two semicircles along its direction of movement, winds on the right semicircle will be in the same direction of the storm's translation motion while winds over the left semicircle will be in the opposite direction. As a result of the superposition of the cyclonic winds and the translational motion of the storm, winds on the right semicircle are usually stronger than those on the left semicircle, which are thus termed the dangerous semicircle and navigable semicircle respectively[1].

Furthermore, in the western North Pacific and the South China Sea, subtropical ridge usually stays on the northeastern side of a tropical cyclone, resulting in a tighter pressure gradient and thus stronger winds in between them. As tropical cyclones over the region usually track northwestwards, the dangerous semicircle will overlap with the tight gradient over the northeastern flank of the storm such that winds over the right semicircle will strengthen further (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1

Orographic Effect

Situated along the coast of southern China, Hong Kong is sheltered from the north by east-west oriented mountain ranges inland but faces the open sea to the south. In addition to the frictional effect over land, northerly winds over Hong Kong are usually weaker than southerlies if other factors are held the same. As winds of a tropical cyclone rotate in an anticlockwise direction in the Northern Hemisphere, prevailing winds are usually southeasterlies and thus stronger when a tropical cyclone lands to the west of Hong Kong. In contrast, relatively weaker northwesterly winds will prevail when a tropical cyclone makes landfall to the east of Hong Kong.

Storm Surge

An offshore rise of water can be induced by the winds of a tropical cyclone and the low pressure near its centre. This effect is called a storm surge. (For details, please refer to the past article "What is a storm surge?" at the Observatory's Blog.)[2] When a tropical cyclone lands to the west of Hong Kong, prevailing southeasterly winds will push on the sea surface and pile up sea water over the coast. Coupled with the low pressure centre of the storm, serious storm surge can be resulted. On the contrary, when a tropical cyclone makes landfall to the east of Hong Kong, prevailing northwesterly winds will push offshore water back to the sea, thus counteracts the effect of the low pressure. Storm surge is usually insignificant under this circumstance.

Due to the reasons mentioned above, tropical cyclones which make landfall to the west of Hong Kong usually bring more severe weather to our region than those land to our east. Table 1 compares the impacts to Hong Kong brought by two tropical cyclones with similar intensity but different landing locations.

Nonetheless, each tropical cyclone is unique. It is not appropriate to conclude that storms landing to our east will bring lesser threat to us. Apart from the location of landfall, the impact of a storm to Hong Kong includes many factors, like the structure and intensity of the storm, the distance of the storm centre from Hong Kong, the distribution of its spiral rainbands etc. Take an example, in July of 2001, although Typhoon Utor made landfall to the east of Hong Kong (near Shanwei), the No. 8 NE, NW and SW Gale or Storm Signals were issued successively and winds over the territory generally reached strong to gale force. A number of trees and scaffolding were toppled. The rainbands of Utor also brought more than 150 mm of rainfall to most parts of the territory. All in all, whenever a storm is approaching Hong Kong, even though it is forecast to land to our east, we should maintain vigilant and should not underestimate the associated severe weather.

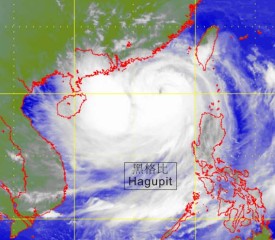

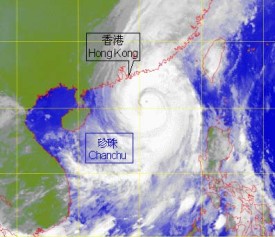

| Name | Hagupit | Chanchu |

|---|---|---|

| Class | Typhoon (Belonged to Severe Typhoon at its peak intensity if based on the new typhoon classification introduced in 2009) | Typhoon (Belonged to Super Typhoon at its peak intensity if based on the new typhoon classification introduced in 2009) |

| Year | 2008 | 2006 |

| Satellite Imagery |  |

|

| Similarities | ||

| Closest Approach to Hong Kong | Around 200 km | Around 200 km |

| Maximum Sustained Winds near the Centre During Closest Approach | Around 170 km/h | Slightly weakened, but the maximum sustained winds near the centre still reached around 170 km/h |

| Differences | ||

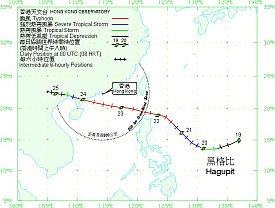

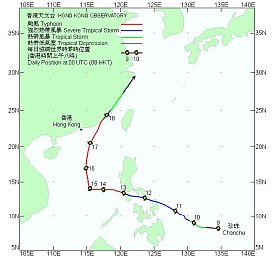

| Track |  |

|

| Landfall | Near Dianbai in Western Guangdong, around 350 km from Hong Kong | Near Shantou, around 300 km from Hong Kong |

| Highest TC Signal | No. 8 NE Gale or Storm Signal, No. 8 SE Gale or Storm Signal | Strong Wind Signal No. 3 |

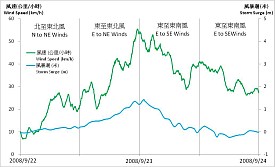

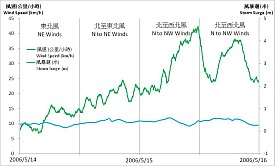

| Wind Direction and Maximum Hourly Wind Speed: Harbour | Easterly Winds, 54 km/h | Northerly Winds, 41 km/h |

| Wind Direction and Maximum Hourly Wind Speed: Cheung Chau | Easterly Winds, 108 km/h | North-Northwesterly Winds, 62 km/h |

| Maximum Storm Surge: Quarry Bay | 1.43 m | 0.59 m |

| Winds at Harbour and Storm Surge Recorded at Quarry Bay |  |

|

Table 1: Comparison of tropical cyclones that made landfall to the east and the west of Hong Kong