The great rainstorm of the century in 1889

20 December 2016

Over the past century, Hong Kong has experienced a number of severe rainstorms. Previously, we have talked about the phenomenal rainstorm on 19 July 1926[1] of which daily rainfall of 534.1 mm were recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory. However, there is a fiercer storm - the great rainstorm of the century on 29-30 May 1889 which beats the 1926 rainstorm in rainfall records with the total rainfall reaching 697.1 mm in 24 hours, amounting to one third of the yearly rainfall!

Record-breaking Rainfall

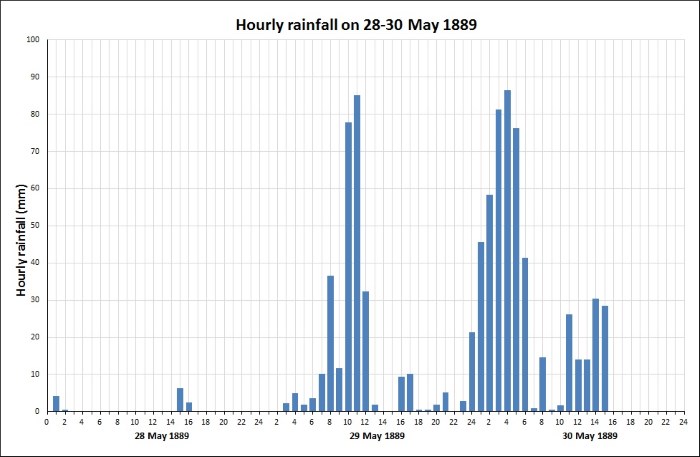

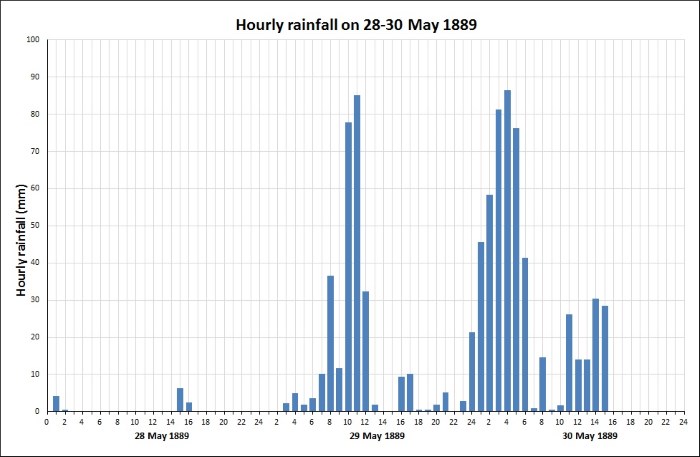

According to the weather log of the Hong Kong Observatory[2, 3], this great rainstorm of the century started in the small hours of 29 May 1889 with continuous thunderstorms moving from southwest to northeast affecting Hong Kong. After a lull period between 2 and 3 p.m., moderate rain returned and lasted till midnight. Then another batch of severe thunderstorms raged across the territory between 1 and 5 a.m. on 30 May. Besides torrential rain, lightning flashed incessantly and thunder roared throughout the night. While the downpour became less intense after 6 a.m., the rain did not stop until late afternoon that day.

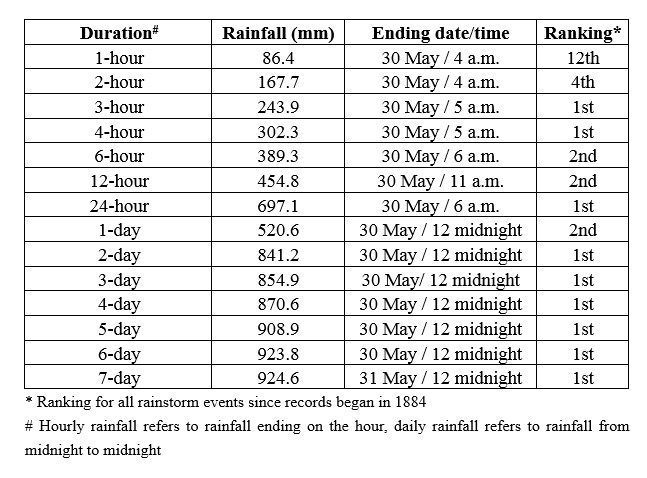

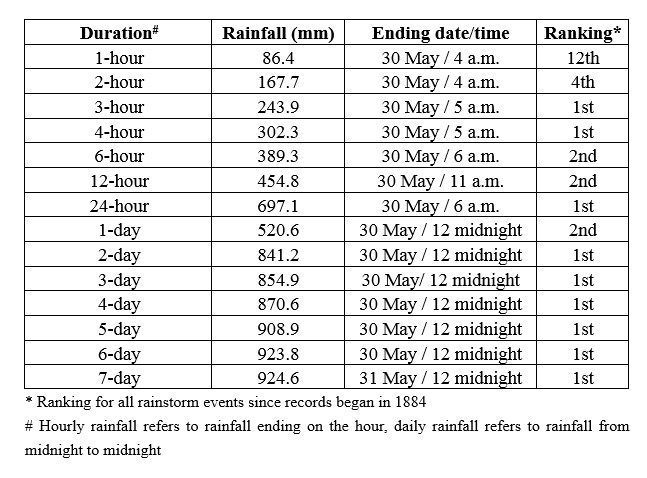

The rainstorm event remains the keeper of many rainfall records at the Hong Kong Observatory, including running 3-hour rainfall, running 4-hour rainfall, running 24-hour rainfall, and 2-day to 7-day rainfall (please see Table 1 for details). Considering the 30-year average annual rainfall at the Observatory at the time (i.e. 1884-1913) of 2113 mm, this great rainstorm of the century essentially brought one third of the yearly rainfall just within 24 hours! This is also a record in itself.

According to the comprehensive report on the rainstorm compiled by Mr. Samuel Brown[4], the Surveyor General (later Director of Public Works) at the time, the rainfall over Hong Kong Island, in particular on the hill slopes, was probably even higher than that of the Observatory in Kowloon. Unfortunately, the raingauge at the Victoria Peak overflowed during the heavy downpour and only an estimated 24-hour rainfall amount of about 707 mm (ending at 10 a.m. on 30 May) was documented in the Observatory's publication[2].

Figure 1Hourly rainfall recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory from 28 to 30 May 1889.

Table 1Maximum rainfall of different durations recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory for the May 1889 rainstorm.

Causes of the Rainstorm

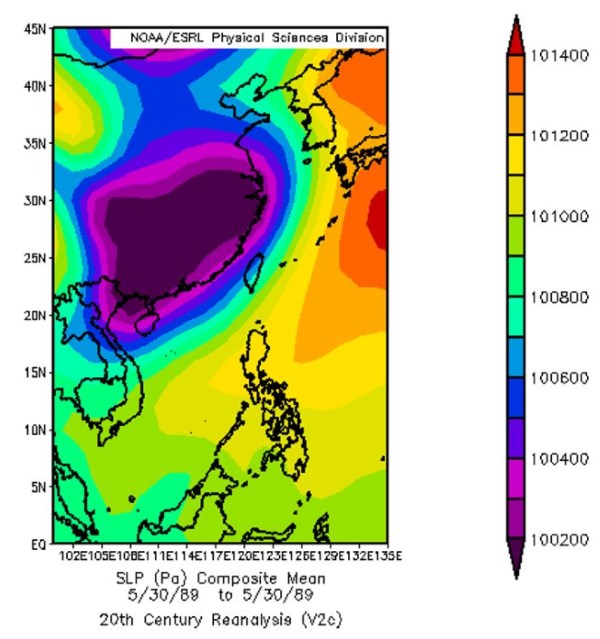

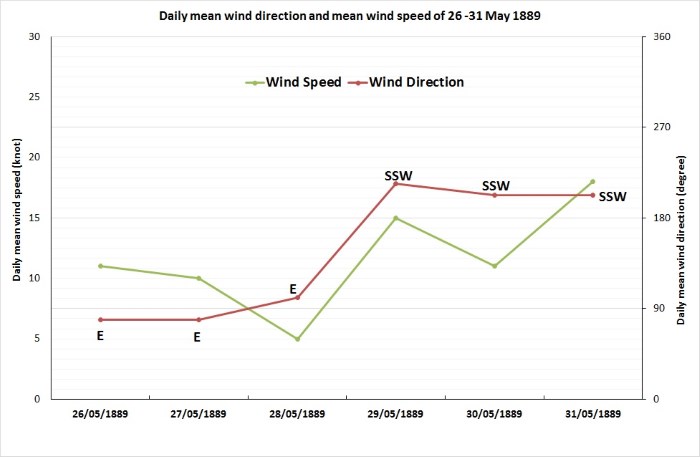

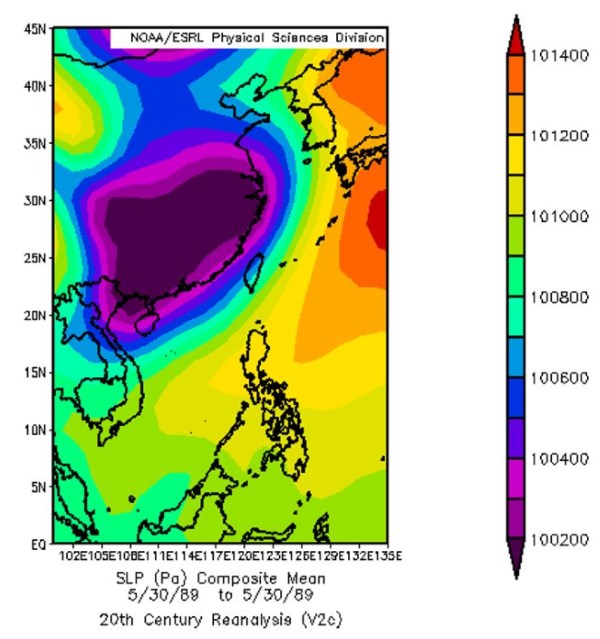

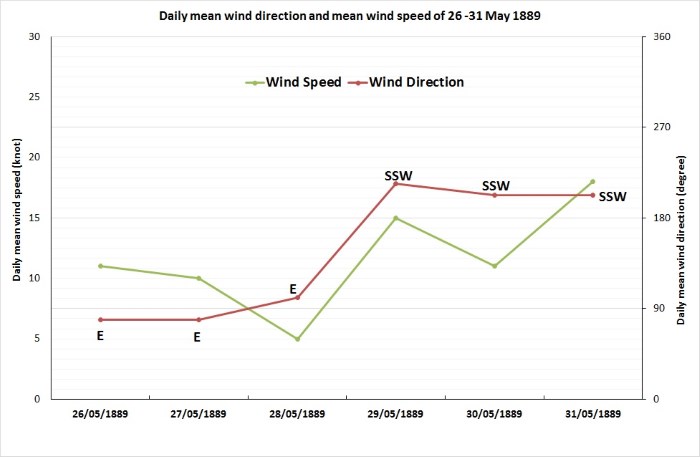

Since this rainstorm happened a long time ago during the late Qing dynasty, only limited weather observations, mostly from the Observatory headquarters at Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, were available for analysis of the weather pattern at the time. The daily mean pressure at the Observatory fell gradually from 1007.9 hPa on 26 May to 1003.2 hPa on 30 May. A re-analysis of the surface pressure pattern[5] revealed a broad trough of low pressure over central and southern China, with rather tight pressure gradient along the coastal areas on both 29 and 30 May. Winds at the Observatory veered from easterly to southwesterly on 29 May when the heavy rain began. Fresh to strong southwesterly winds were also reported at the Victoria Peak on 29-30 May. In the absence of any reported tropical cyclone activity, the unsettled weather could be attributed to the broad trough, with the enhanced southwest monsoon bringing an ample supply of moisture that sustained the development of the rainstorm over the south China coastal areas.

Figure 2Re-analysis of the surface pressure on 30 May 1889 (source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Earth System Research Laboratory, Physical Sciences Division).

Figure 3Daily mean wind speed and direction at the Hong Kong Observatory from 26 to 31 May 1889.

Damages and Casualties

According to the newspapers[6] and the Surveyor General's report[4], the severe rainstorm on 29-30 May 1889 was one of the most destructive rainstorms in the history of Hong Kong with numerous reports of flooding and landslides. Traffic in the city, telegraph communications and water supply from Tai Tam Reservoir (called Tytam reservoir at the time) were interrupted. Consequently, some people were obliged to use muddy water that was flowing down the side channels and the streams as their source of water supply[3], bringing serious impacts to the society and people's livelihood.

Landslides

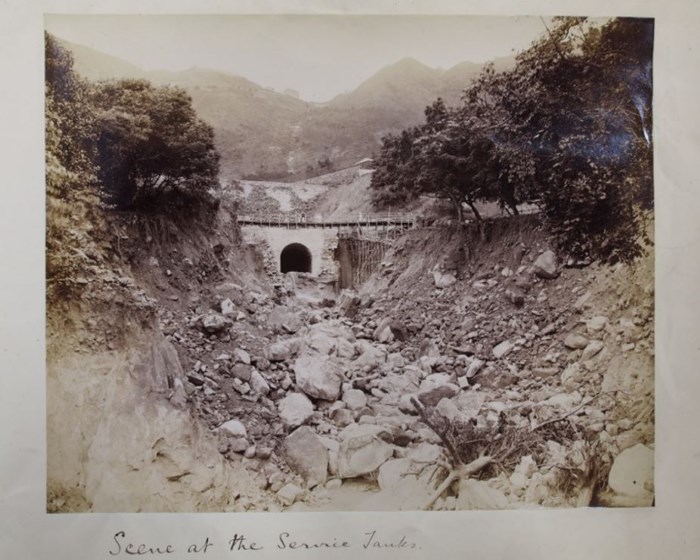

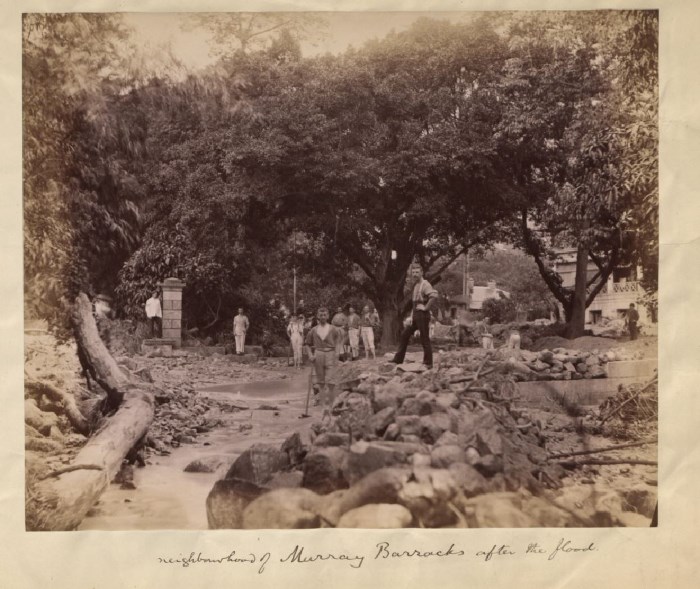

Over Hong Kong Island, torrents of rain water mixed with debris severely damaged the Glenealy Nullah and the Albany Nullah located at the mid-levels. For Albany Nullah (starting around point A in Figure 4), the Tytam service tank and filter beds above the Bowen and Garden Roads (point C in Figure 4; photo in Figure 5) were severely damaged by landslides from the steep slope (photo in Figure 6) immediately below the Rural Building Lot No. 7 (point D in Figure 4) and filled up by rock and debris on 29 May. This led to even more serious landslides and heavy rush of water when yet heavier rain fell during the night and early morning of 30 May. An estimated 13,800 cubic metres of earth was washed away from the slopes of the service tank and filter beds while another equal quantity was probably washed away from the banks of the nullah below the service tank. As a result, part of the tramway connecting the city and the Peak together with two bridges were swept away. The torrents wreaked havoc at the Murray Barracks (around point E in Figure 4, photo in Figure 7) which was flooded to around 0.6 -1.2 metre where order was given to evacuate the quartered servicemen and stores from the basement floors.

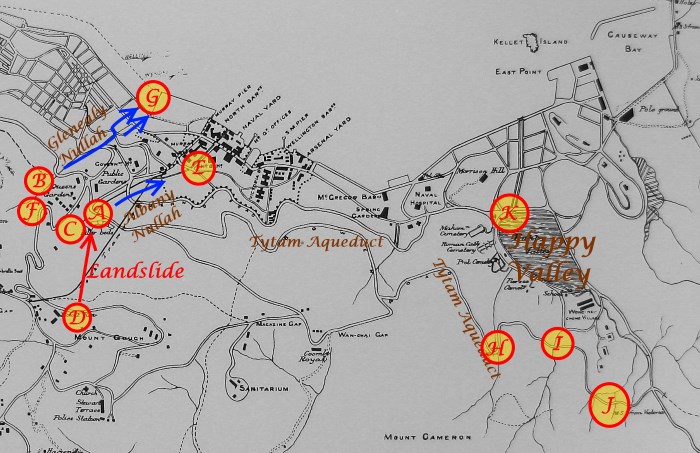

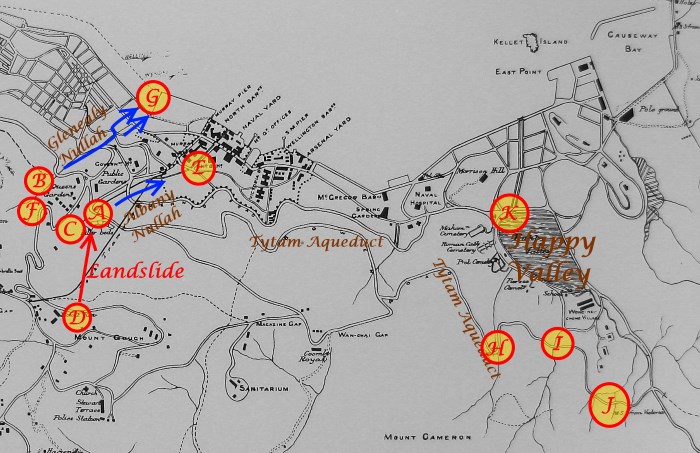

Figure 4Diagram showing the locations of the major damages at the Glenealy Nullah, Albany Nullah, Tytam Aqueduct (along Bowen Road) and Happy Valley.

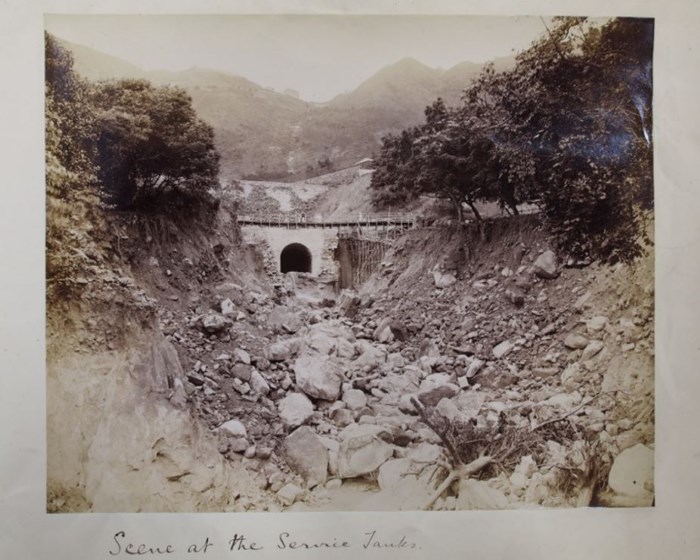

Figure 5Damage to the Tytam service tank (source: National Archives, UK).

Figure 6Landslides above the Tytam service tank (source: National Archives, UK).

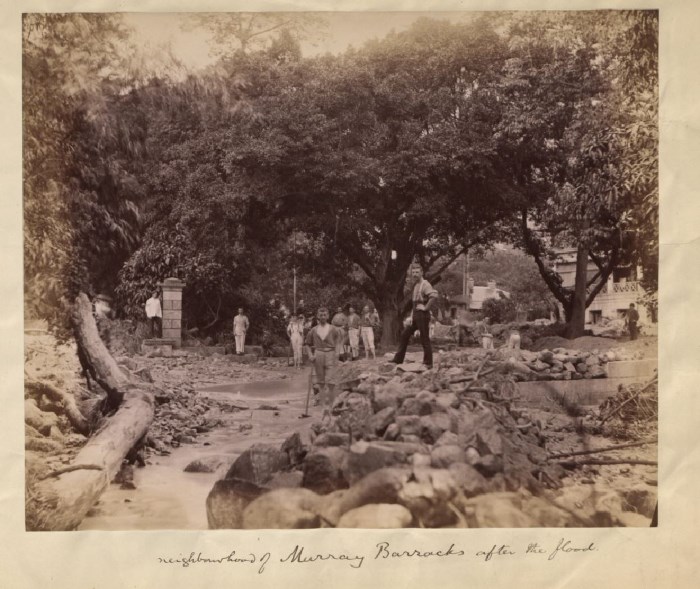

Figure 7Neighbourhood of Murray Barracks after the rainstorm (source: CM Shun).

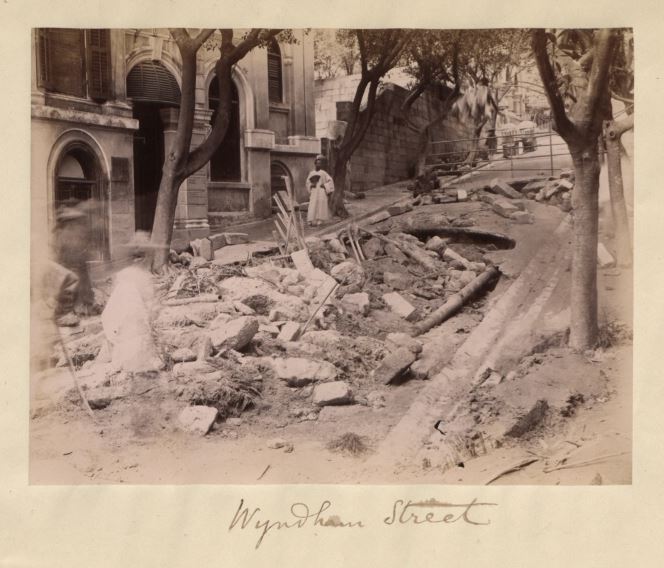

Over the Glenealy Nullah (starting near point B in Figure 4, photo in Figure 8) located about 640 metres to the west of the Albany Nullah, the amount of water running down the ravine was considerably augmented due to the ongoing building construction work uphill (near point F in Figure 4). The floods and landslides at the mid-levels and downstream areas deposited large amount of debris in Wyndham Street (photo in Figure 9), Queen's Road Central and Pedder Street (around point G in Figure 4; photo in Figure 10). At Zetland Street (Figure 11), the torrents flooded the street to around 1.5-1.8 metre, tore up the roadway and ploughed up the bottom to a depth of 1.5-1.8 metre.

Figure 8Damage to the Glenealy Nullah (source: National Archives, UK).

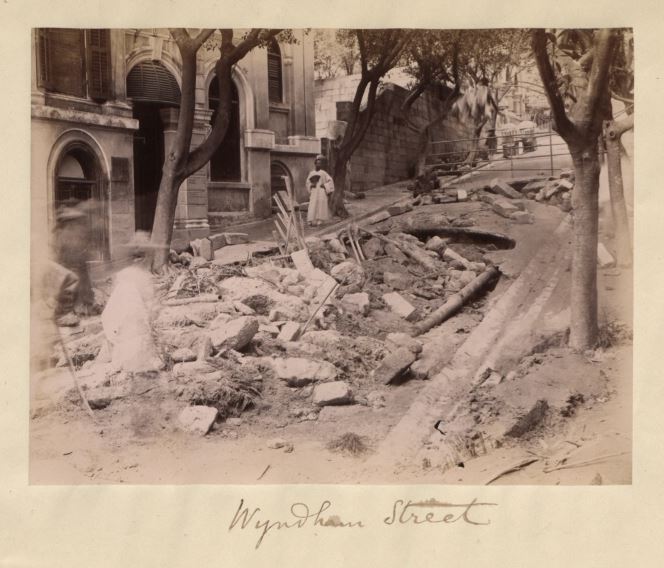

Figure 9Debris on Wyndham Street in Central after the rainstorm (source: National Archives, UK).

Figure 10Pedder Street in Central after the rainstorm (source: National Archives, UK).

Figure 11An artist's impression of the torrents at Zetland Street, Central (source: CM Shun).

Serious landslides also occurred along the steep slopes above the Tytam Aqueduct along Bowen Road where the masonry of the aqueduct was damaged in three places (near points H, I and J in Figure 4), involving some 23,000 cubic metres of debris. One of these slides involving 3,800 cubic metres of debris swept through the Hong Kong Cemetery all the way onto the racecourse in Happy Valley (around point K in Figure 4). Landslides also affected parts of Wanchai, Western District and Kennedy Town. The Surveyor General estimated that some hundreds of landslides of various sizes had probably occurred over Hong Kong in this great rainstorm of the century.

Casualties and Remedial Works

It was estimated that a total of 27 people were killed, including six coolies killed by lightning at the Peak, and another 17 were missing[4, 7]. The remedial work were mostly handled by Mr. S. Brown (the Surveyor General), Mr. F. A. Cooper (Acting Assistant Surveyor General), and Lieut. Colonel H. Champernowne (Royal Engineer). The cost of damage to government property was estimated at a total amount of $112,783 at the time which amounted to about 6% of the annual expenditure of the Government in 1889[4, 8].

Water Supply

As water supply from Tai Tam Reservoir was interrupted, people had to rely on the Pokfulam Reservoir supply. However, as muds went into the reservoir, the quality of water became a major concern. Water quality tests were immediately done[9]. Water supply thus became the top priority of the Surveyor General[10]. Thus, one of the major outcomes of the 1889 rainstorm was the establishment of the Water and Drainage Department in 1890 to handle drinking and foul water[11].

Concluding Remarks

The rainfall records set by this great rainstorm of the 19th Century and the associated damages were indeed rather alarming. A number of the associated rainfall records have yet to be broken. Under the trend of the intensifying climate change, extreme weather events including rainstorms are becoming more frequent. Past rainfall records, including the 1-hour and running 2-hour rainfall records, had already been broken in recent years. Recurrence of the great rainstorm of the century will only be a matter of time.

Recently, Mr Wong Hok Ning, Head of the Geotechnical Engineering Office, who is about to retire, also described landslip as a "sleeping lion" which seemed to be waking up, and even though the risk of landslide was in general higher for man-made slopes, natural slopes would have greater response when the rainfall reached a certain level, leading to landslides[12]. Recalling that the Surveyor General estimated that some hundreds of landslides of various sizes had probably occurred over Hong Kong in the great rainstorm of 1889, are we fully prepared if this or an even greater rainstorm were to recur in the foreseeable future? Facing the increasing risks brought by climate change, indeed we will need to increase our alertness and preparedness, and to enhance public education so that Hong Kong will be resilient and climate ready.

T.C. Lee, C.M. Shun and K.Y. Ma*

(* Mr K.Y. Ma is a retired government engineer and also an enthusiast in the history of engineering in Hong Kong. He is currently Adjunct Associate Professor at the Department of Real Estate and Construction, University of Hong Kong)

References

[1] The Phenomenal Rainstorm in 1926 https://www.hko.gov.hk/blog/en/archives/00000135.htm

[2] Hong Kong Observatory, 1890: Observations made at the Hong Kong Observatory in the year 1889.

[3] Chan, C. W., 1976: The rainstorms of May 1889 and July 1926, Royal Observatory Occasional Paper No. 33.

[4] S Brown, 1889: Report on great storm of 29th and 30th May 1889.

[5] 20th Century Re-analysis (V2), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Earth System Research Laboratory, Physical Sciences Division https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/composites/subdaily_20thc/index.html

[6] "After the great storm", China Mail, 31 May 1889.

[7] Ho Pui-yin, 2003: "Weathering the Storm: Hong Kong Observatory and Social Development", Hong Kong University Press, 364 pp.

[8] Hong Kong Government, 1890: Report on the blue book and departmental reports for 1889.

[9] Hong Kong Telegraph, 30 May 1889.

[10] China Mail, 1 June 1889.

[11] Hong Kong Government Gazette No. 215 of 1890.

[12] Sing Tao Daily, 19 December 2016 (in Chinese)

Record-breaking Rainfall

According to the weather log of the Hong Kong Observatory[2, 3], this great rainstorm of the century started in the small hours of 29 May 1889 with continuous thunderstorms moving from southwest to northeast affecting Hong Kong. After a lull period between 2 and 3 p.m., moderate rain returned and lasted till midnight. Then another batch of severe thunderstorms raged across the territory between 1 and 5 a.m. on 30 May. Besides torrential rain, lightning flashed incessantly and thunder roared throughout the night. While the downpour became less intense after 6 a.m., the rain did not stop until late afternoon that day.

The rainstorm event remains the keeper of many rainfall records at the Hong Kong Observatory, including running 3-hour rainfall, running 4-hour rainfall, running 24-hour rainfall, and 2-day to 7-day rainfall (please see Table 1 for details). Considering the 30-year average annual rainfall at the Observatory at the time (i.e. 1884-1913) of 2113 mm, this great rainstorm of the century essentially brought one third of the yearly rainfall just within 24 hours! This is also a record in itself.

According to the comprehensive report on the rainstorm compiled by Mr. Samuel Brown[4], the Surveyor General (later Director of Public Works) at the time, the rainfall over Hong Kong Island, in particular on the hill slopes, was probably even higher than that of the Observatory in Kowloon. Unfortunately, the raingauge at the Victoria Peak overflowed during the heavy downpour and only an estimated 24-hour rainfall amount of about 707 mm (ending at 10 a.m. on 30 May) was documented in the Observatory's publication[2].

Figure 1Hourly rainfall recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory from 28 to 30 May 1889.

Table 1Maximum rainfall of different durations recorded at the Hong Kong Observatory for the May 1889 rainstorm.

Causes of the Rainstorm

Since this rainstorm happened a long time ago during the late Qing dynasty, only limited weather observations, mostly from the Observatory headquarters at Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, were available for analysis of the weather pattern at the time. The daily mean pressure at the Observatory fell gradually from 1007.9 hPa on 26 May to 1003.2 hPa on 30 May. A re-analysis of the surface pressure pattern[5] revealed a broad trough of low pressure over central and southern China, with rather tight pressure gradient along the coastal areas on both 29 and 30 May. Winds at the Observatory veered from easterly to southwesterly on 29 May when the heavy rain began. Fresh to strong southwesterly winds were also reported at the Victoria Peak on 29-30 May. In the absence of any reported tropical cyclone activity, the unsettled weather could be attributed to the broad trough, with the enhanced southwest monsoon bringing an ample supply of moisture that sustained the development of the rainstorm over the south China coastal areas.

Figure 2Re-analysis of the surface pressure on 30 May 1889 (source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Earth System Research Laboratory, Physical Sciences Division).

Figure 3Daily mean wind speed and direction at the Hong Kong Observatory from 26 to 31 May 1889.

Damages and Casualties

According to the newspapers[6] and the Surveyor General's report[4], the severe rainstorm on 29-30 May 1889 was one of the most destructive rainstorms in the history of Hong Kong with numerous reports of flooding and landslides. Traffic in the city, telegraph communications and water supply from Tai Tam Reservoir (called Tytam reservoir at the time) were interrupted. Consequently, some people were obliged to use muddy water that was flowing down the side channels and the streams as their source of water supply[3], bringing serious impacts to the society and people's livelihood.

Landslides

Over Hong Kong Island, torrents of rain water mixed with debris severely damaged the Glenealy Nullah and the Albany Nullah located at the mid-levels. For Albany Nullah (starting around point A in Figure 4), the Tytam service tank and filter beds above the Bowen and Garden Roads (point C in Figure 4; photo in Figure 5) were severely damaged by landslides from the steep slope (photo in Figure 6) immediately below the Rural Building Lot No. 7 (point D in Figure 4) and filled up by rock and debris on 29 May. This led to even more serious landslides and heavy rush of water when yet heavier rain fell during the night and early morning of 30 May. An estimated 13,800 cubic metres of earth was washed away from the slopes of the service tank and filter beds while another equal quantity was probably washed away from the banks of the nullah below the service tank. As a result, part of the tramway connecting the city and the Peak together with two bridges were swept away. The torrents wreaked havoc at the Murray Barracks (around point E in Figure 4, photo in Figure 7) which was flooded to around 0.6 -1.2 metre where order was given to evacuate the quartered servicemen and stores from the basement floors.

Figure 4Diagram showing the locations of the major damages at the Glenealy Nullah, Albany Nullah, Tytam Aqueduct (along Bowen Road) and Happy Valley.

Figure 5Damage to the Tytam service tank (source: National Archives, UK).

Figure 6Landslides above the Tytam service tank (source: National Archives, UK).

Figure 7Neighbourhood of Murray Barracks after the rainstorm (source: CM Shun).

Over the Glenealy Nullah (starting near point B in Figure 4, photo in Figure 8) located about 640 metres to the west of the Albany Nullah, the amount of water running down the ravine was considerably augmented due to the ongoing building construction work uphill (near point F in Figure 4). The floods and landslides at the mid-levels and downstream areas deposited large amount of debris in Wyndham Street (photo in Figure 9), Queen's Road Central and Pedder Street (around point G in Figure 4; photo in Figure 10). At Zetland Street (Figure 11), the torrents flooded the street to around 1.5-1.8 metre, tore up the roadway and ploughed up the bottom to a depth of 1.5-1.8 metre.

Figure 8Damage to the Glenealy Nullah (source: National Archives, UK).

Figure 9Debris on Wyndham Street in Central after the rainstorm (source: National Archives, UK).

Figure 10Pedder Street in Central after the rainstorm (source: National Archives, UK).

Figure 11An artist's impression of the torrents at Zetland Street, Central (source: CM Shun).

Serious landslides also occurred along the steep slopes above the Tytam Aqueduct along Bowen Road where the masonry of the aqueduct was damaged in three places (near points H, I and J in Figure 4), involving some 23,000 cubic metres of debris. One of these slides involving 3,800 cubic metres of debris swept through the Hong Kong Cemetery all the way onto the racecourse in Happy Valley (around point K in Figure 4). Landslides also affected parts of Wanchai, Western District and Kennedy Town. The Surveyor General estimated that some hundreds of landslides of various sizes had probably occurred over Hong Kong in this great rainstorm of the century.

Casualties and Remedial Works

It was estimated that a total of 27 people were killed, including six coolies killed by lightning at the Peak, and another 17 were missing[4, 7]. The remedial work were mostly handled by Mr. S. Brown (the Surveyor General), Mr. F. A. Cooper (Acting Assistant Surveyor General), and Lieut. Colonel H. Champernowne (Royal Engineer). The cost of damage to government property was estimated at a total amount of $112,783 at the time which amounted to about 6% of the annual expenditure of the Government in 1889[4, 8].

Water Supply

As water supply from Tai Tam Reservoir was interrupted, people had to rely on the Pokfulam Reservoir supply. However, as muds went into the reservoir, the quality of water became a major concern. Water quality tests were immediately done[9]. Water supply thus became the top priority of the Surveyor General[10]. Thus, one of the major outcomes of the 1889 rainstorm was the establishment of the Water and Drainage Department in 1890 to handle drinking and foul water[11].

Concluding Remarks

The rainfall records set by this great rainstorm of the 19th Century and the associated damages were indeed rather alarming. A number of the associated rainfall records have yet to be broken. Under the trend of the intensifying climate change, extreme weather events including rainstorms are becoming more frequent. Past rainfall records, including the 1-hour and running 2-hour rainfall records, had already been broken in recent years. Recurrence of the great rainstorm of the century will only be a matter of time.

Recently, Mr Wong Hok Ning, Head of the Geotechnical Engineering Office, who is about to retire, also described landslip as a "sleeping lion" which seemed to be waking up, and even though the risk of landslide was in general higher for man-made slopes, natural slopes would have greater response when the rainfall reached a certain level, leading to landslides[12]. Recalling that the Surveyor General estimated that some hundreds of landslides of various sizes had probably occurred over Hong Kong in the great rainstorm of 1889, are we fully prepared if this or an even greater rainstorm were to recur in the foreseeable future? Facing the increasing risks brought by climate change, indeed we will need to increase our alertness and preparedness, and to enhance public education so that Hong Kong will be resilient and climate ready.

T.C. Lee, C.M. Shun and K.Y. Ma*

(* Mr K.Y. Ma is a retired government engineer and also an enthusiast in the history of engineering in Hong Kong. He is currently Adjunct Associate Professor at the Department of Real Estate and Construction, University of Hong Kong)

References

[1] The Phenomenal Rainstorm in 1926 https://www.hko.gov.hk/blog/en/archives/00000135.htm

[2] Hong Kong Observatory, 1890: Observations made at the Hong Kong Observatory in the year 1889.

[3] Chan, C. W., 1976: The rainstorms of May 1889 and July 1926, Royal Observatory Occasional Paper No. 33.

[4] S Brown, 1889: Report on great storm of 29th and 30th May 1889.

[5] 20th Century Re-analysis (V2), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Earth System Research Laboratory, Physical Sciences Division https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/composites/subdaily_20thc/index.html

[6] "After the great storm", China Mail, 31 May 1889.

[7] Ho Pui-yin, 2003: "Weathering the Storm: Hong Kong Observatory and Social Development", Hong Kong University Press, 364 pp.

[8] Hong Kong Government, 1890: Report on the blue book and departmental reports for 1889.

[9] Hong Kong Telegraph, 30 May 1889.

[10] China Mail, 1 June 1889.

[11] Hong Kong Government Gazette No. 215 of 1890.

[12] Sing Tao Daily, 19 December 2016 (in Chinese)